National Geographic: Remembering the Woman Who Helped Bears in Distress

Bears smile just like we do, said Else Poulsen, who understood what makes them tick.

If ever there was a bear whisperer, Poulsen was one. She raised bears, comforted bears, taught bears, learned from bears, had bears communicate their needs to her, and nursed bears back to health. She shared in the joy of a polar bear discovering soil under her paws for the first time in 20 years, felt the pride of a cub learning to crack nuts with her molars.

She also grieved at the barbarity of captivity for Asian black bears in China and Vietnam, which is how she and I bonded, as I’d been researching bear bile trafficking and bile farms for my book Animal Investigators.

“Nothing stumped her,” says Jill Robinson, who often sought Poulsen’s advice. Robinson is the founder of Animals Asia Foundation, a Hong Kong-based organization that rescues bears from bile farms. “No challenge was too hard. Her abiding principle was to ask the bears themselves, ‘What can I do for you?’”

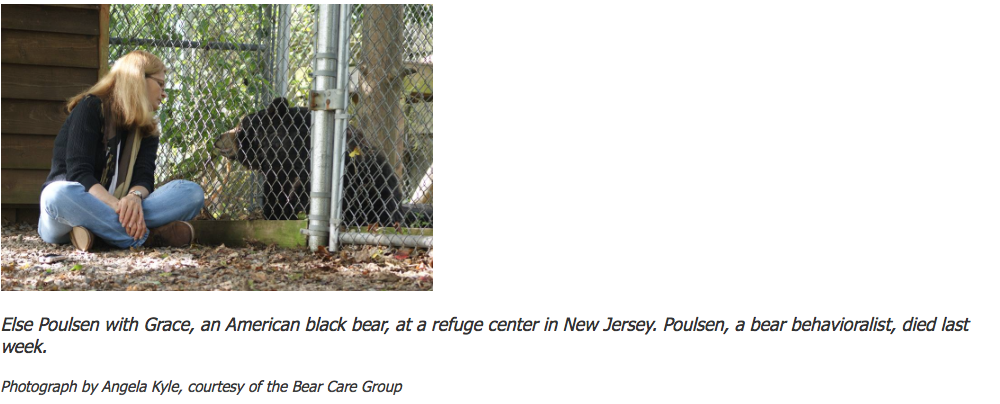

Best known for rehabilitating bears from the psychological trauma of captivity, Poulsen dedicated her life to improving their quality of life. She did this through her work as a zookeeper at the Calgary and Detroit Zoos and in one-on-one consulting with zoos, sanctuaries, and wildlife rehabilitators, where she helped bears in distress. She was generous with advice and was the founding president of the Bear Care Group, a network of international bear care professionals who shared experiences and information to improve bear welfare and conservation worldwide.

She also brought bears to light through her writing, which included many professional papers and two books: Smiling Bears: A Zookeeper Explores the Behaviour and Emotional Life of Bears and Bärle's Story: One Polar Bear's Amazing Recovery from Life as a Circus Act.

In 2010 Poulsen shared her thoughts about how a bear’s behavior reflects its emotional life. Following are excerpts from that conversation.

How did you first get interested in bears?

I tend to think that bears picked me. When I started in the early 1980s at the Calgary Zoo, we had a four-year apprenticeship program where you worked with everything from toads to tigers. There were no college or university courses in this. As I worked my way through the zoo and learned about the husbandry and natural behavior of all the animals, I found myself understanding large carnivores better [than other types of animals].

There are some people who can look at a toad and say, "Yep, that toad is sick." Me? I’d look at a toad and think it was perfectly healthy, and the next day it would have its legs up in the air and be dead. I just didn't have a good feel for amphibians. But I did for large carnivores, and over time I realized that I seemed to understand bears better.

People always ask zookeepers who their favorite animal is. For myself, and for many other keepers, it's the animal that needs you the most.

Who was one of the bears that needed you?

Miggy was an American black bear cub who arrived motherless at the Detroit Zoo. She was eight months old and small for her age. She was going to be introduced to other bears, so it was imperative to be with her when she was eating [to teach her how to share]. We would crack nuts together. I did it with a rock and then showed her there was something inside. One day she was in a mood and not her usual jovial self. She started cracking nuts. Then she made this gutteral noise and bit my hand. That was her signal to stop doing whatever it was I was doing and watch her while she demonstrated the bear way of doing things. She picked up the walnut, crunched it, and spat it out—as if to say that’s the bear way of cracking a nut. Her genetics had kicked in.

How did you come to learn about the emotional lives of bears?

It's taken a lot of time spent knowing bears personally in the captive community, and it has happened little by little. It's embarrassing to say that it took several years of working around bears before I understood that they smile. Bears smile just like we do. They pull each side of their mouth upwards. They smile for their reasons of self-contentment, just like we humans smile for our reasons of self-contentment. It's just that our reasons may not be the same.

A human mother may smile if her child does something that she finds funny. A bear mom will smile if her cubs do something cute or something that she finds contentment in. That's the similarity. But in other cases, a grizzly bear in Montana might smile when he reaches the top of the mountain and finds thousands and thousands of larvae up there that he can eat. I wouldn't be smiling about that. It doesn't mean anything to me. Bears express emotion based on what matters to them in their bear world.

Intrinsically, we recognize anger and annoyance in a bear as growling or spitting or standing on its hind legs and giving you the evil eye and maybe batting at the air or something like that. We're used to seeing it in the movies. But we as a society have been slow to allow animals to have the converse feelings of love, happiness, joy—those kinds of things. We think only humans can have those feelings.

What lesson has your work taught you about bears?

Every bear is an individual just like every human is an individual. There are really three parts of a bear's personality. [The first is] genetic programming. Every bear is utterly and completely convinced of being a bear. Polar bears have a genetic expectation to live in an Arctic environment. Sun bears have an expectation to live in the jungle. Panda bears have an expectation to eat bamboo. With bears there is also a nature versus nurture. Mom will take her youngster around and show the youngster what parts of the environment are useful and how to use it. That's one aspect of it.

Another aspect making up a bear’s personality is personal history. Bears are smart, just like we are, and our personal history has a huge bearing on what we do, just like for bears.

The last part of what makes up a bear is the current environment. Just like with us, we have our history and genetics, and then our current environment dictates how we use all of those things and how we behave, and that's true for bears as well.

I think the reason I wrote Smiling Bears was to show people just how sensitive bears truly are, and that every bear is an individual made up of these things. If people recognize that, then they'll want to conserve bears.

Laurel Neme is a freelance writer and author of Animal Investigators: How the World’s First Wildlife Forensics Lab Is Solving Crimes and Saving Endangered Species and Orangutan Houdini. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook.